Unlock this story — it’s free

The international hunting income’s continued support for Tanzanian rural communities’ socio-economic and conservation needs is still the answer to their developmental needs.

Tanzania has emerged as one of the African hunting countries with the most resilient international hunting industry that continued operating even during the COVID-19 international travel bans with a few adrenaline-chasing international hunters having travelled to hunt there.

Looking back at Tanzania’s formative years of benefits from international hunting, it has becomes evident that only industries that don’t benefit the people die. But Tanzania’s international hunting industry is not one of them.

In 1998, the Tanzanian government announced its political will to allow the rural communities to start benefiting from their natural resources, including wildlife largely through international hunting.

“This involves the establishment of wildlife management areas by the Department of National Parks, working together with the communities,” said Deborah Kahatano, Programme Officer for the Environment Policy and Industrial Strengthening Project (1999), now working for the United Nations Environment Programme.

Twenty-six years ago (1998), the local, regional and international conservationists welcomed the Tanzanian government’s breath-of-fresh-air democratisation of conservation and development policy.

“We are involving people in the conservation of natural resources, particularly wildlife and we hope that one day, they will use money generated from these conservation projects to build infrastructure according to community needs,” said Peter Tolma, Director of the Maasai Advancement Association (1999).

There was great hope that international hunting revenue would later help support the Maasai communities by turning their dry and agriculturally unproductive land into an international hunting industry magnate, with wildlife as the number one draw-card.

Describing the almost hopeless economic status of the Maasai communities 26 years ago in the absence of international hunting industry, Toima said, “The Maasai lack schools, roads and communication facilities. They have no safe water, either for humans or livestock. The areas are characterised by poor rainfall patterns.”

Today they have them all, brought by international hunting dollars.

However, when I interviewed Toima 26 years ago, I could not imagine how hunted monkeys, baboons, hyenas, lions, elephants, buffaloes and other wild animals could bring water and income to build schools, clinics and even support the conservation of their own habitat [wilderness areas].

I was a young, curious and budding environmental journalist with great interest to see how international hunting dollars would support conservation and development in geographically disadvantaged Maasai communities.

When I visited one of their communities I never saw a running river. The land was just not suitable for crop production. Even cattle-grazing pastures were scarce and the cattle had to be driven for grazing from place to place, seasonally.

I have been following with great interest, the international hunting-supported conservation and development initiatives progress in Tanzania since 1998.

Today, the Maasai communities are receiving significant benefits from the revenue generated from international hunting. I now know how even the smallest hunted wildlife and also the biggest land mammal [elephant] can contribute towards building a school, road and even support the conservation of its surviving relatives’ wilderness habitat.

For people who have not witnessed these benefits, it’s almost too good to be true. But that’s the truth. In Tanzania, international hunting revenue’s continued community socio-economic development and conservation needs support is the correct and practical incentive to help cultivate a culture of wildlife conservation.

Today, 26 years later, what do Tanzanian local communities co-existing with wildlife say about international hunting benefits?

They highlight the hunting income’s support for the construction of schools, provision of medical facilities, water, electricity and employment creation.

These, together with the community ownership and conservation of wildlife are the life-changing benefits that international hunting has brought to Tanzanian wildlife-producer communities in the 21st century, confirms the East African country’s top NGO that represents wildlife-producer-communities.

“International hunting is supporting the construction of medical facilities as dispensaries, building schools and social services like water and electricity supply,” says a representative of the Community Wildlife Management Areas Consortium of Tanzania, Mr Mohammed Kamona in a recent interview.

He says that the hunting revenue “meets the needs that communities are lacking.”

The Community Wildlife Management Areas Consortium of Tanzania is a top NGO which works with local communities and the Tanzanian Government whose role is to ensure that community wildlife management policies are being implemented correctly.

“We are doing different kinds of sustainable use activities and one of them is international hunting,” says Mr Kamona. “The communities’ attitude to wildlife when they benefit, is very positive in a sense that these communities have been living with wildlife even before I was born, even before my grandfather was born.”

Mr Kamona says that hunting has always been part of Tanzanian people’s tradition.

“If there are people who oppose hunting, they have to realise that there are communities that depend on wildlife for their livelihoods,” says Mr Kamona in an apparent warning against the animal rights extremist NGOs’ wildlife-harming opposition to international hunting.

“Just like they depend on vehicles for their transport, it’s just the same with Tanzanian people who also depend on wildlife for their livelihoods.

“We have to acknowledge and recognise the importance of sustainable use for the people who co-exist and depend on wildlife.”

He says that “it is unfair for anyone to dictate to other people” not to use their wildlife.

“We have to respect the concept of sustainable use and it’s good that the Tanzanian Government has included international hunting as one of the sustainable use mechanisms,” notes Mr Kamona.

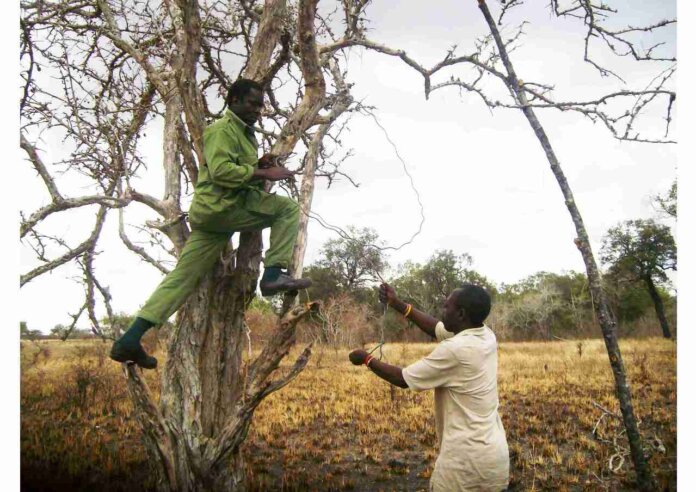

In Tanzanian communities where international hunting takes place, hunted wildlife and the revenue it generates ‘teach’ local residents not to poach wildlife and always set aside beautiful ‘homes’ for them in the form of wildlife habitats.

“The hunting community residents from Tanzania who used to be poachers but no longer poach because they are now enjoying the socio-economic benefits from hunting include the Waikoma, Wakurya, Waisenyi, Wananta and Wangoreme tribes that border the Ikorongo/Gurumeti Game Reserve in the western part of Serengeti National Park,” says a Tanzanian citizen Dr. Ladislaus Kahana, who is a senior lecturer at College of African Wildlife Management Mweka.