By: Bongani Dinga Ka Luvatsha

South Africa had in the past recognised two different systems of succession: the common law (together with the statutes amending it) and customary law.

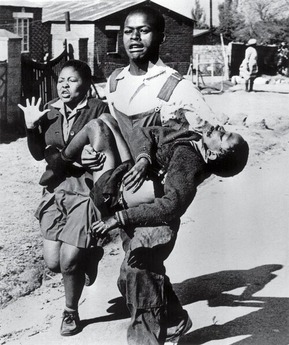

Many of the customary law rules previously used were not only in conflict with the principle of equal treatment, but totally unconstitutional. The debate concerning the conflict between culture and equality has been widely debated in case law especially in the last few years.

A concrete example of the conflict surfaced is the first case of Mthembu v Letsela, as well as the second Mthembu case (Mthembu v Letsela), Bhe v The Magistrate of Khayelitsha, which went on appeal. Ultimately, as discussed above, the discriminatory statutory and customary law rules were declared unconstitutional and new legislation promulgated.

However, analysis of the impact of these documents should not be superficial because, as much as practices and culture are fluid and dynamic, the question should not be whether they have changed, but rather how they have changed and whether such changes have disrupted existing power relations (which favour men) within the community. As indicated with the example of customary marriages, although the practice of marriage may be changing, it has not translated into increasing levels of power for women. Rather, other practices and discourses (such as primogeniture) are used to maintain male power and land ownership. Though since the rule of male primogeniture has been abolished after Bhe case but in most parts of Africa and South Africa in particular the rule is still practiced.